26 February 2022 at 2:49 PM

High Country of High Knob Massif

Looking West From Eagle Knob Summit

Cody Blankenbecler Image © All Rights Reserved

Double digit February precipitation has been observed for the fourth time in five years within

the high country of the High Knob Massif.

26 February 2022 at 2:49 PM

High Country of High Knob Massif

Looking West From Eagle Knob Summit

Cody Blankenbecler Image © All Rights Reserved

Observed February Precipitation

Big Cherry Dam of High Knob Massif

2018: 14.37

2019: 12.50

2020: 13.01

2021: 7.42

2022: 10.32

5-Year Mean: 11.52"

(15-Year February Mean: 7.55")

Around a FOOT of precipitation, in the mean, has now been observed during the five February's from 2018-2022.

26 February 2022 at 2:49 PM

High Country of High Knob Massif

Looking To High Knob Lookout

Cody Blankenbecler Image © All Rights Reserved

Distant and majestic rime coated ridges beyond High Knob Lookout Tower, in Big Cherry Basin, have been mostly within clouds this week.

They did briefly appear before cross-barrier

flow increased in advance of more significant precipitation.

Reference this section for more details:

23 February 2022

Enhanced Thermal Gradient

High-Eagle Gap Cross-Barrier Flow

Virginia-Kentucky Communications © All Rights Reserved

Precipitation Update

High Knob Massif

(Upper Elevations)

(Totals Listed By AM Measurement Format)

Monthly Total Precipitation

Big Cherry Lake Dam

(Elevation 3139 feet)

2019

January

6.14"

February

12.50"

Winter 2018-19

(1 Dec-29 Feb)

26.56"

March

5.93"

April

6.64"

May

6.75"

Spring 2019

(1 Mar-31 May)

19.32"

June

10.68"

July

10.77"

August

4.15"

Summer 2019

(1 Jun-31 Aug)

25.60"

September

0.63"

October

5.01"

( 5.89" to Midnight 31st )

November

5.20"

( 7.04" to Midnight 30th )

Autumn 2019

(1 Sep-31 Oct)

10.84"

December

8.52"

2019 Total: 82.92" (M)

(January 1 to December 31 Period)

2020

*January

7.15"

**February

13.01"

Winter 2019-20

(1 Dec-29 Feb)

28.68"

March

9.55"

( 10.77" to Midnight 31st )

April

11.59"

May

8.73"

(6.90" on Eagle Knob of High Knob Massif)

Spring 2020

(1 Mar-31 May)

29.87"

June

7.48"

July

9.72"

(10.48" to Midnight 31st)

August

8.12"

Summer 2020

(1 Jun-31 Aug)

25.32"

September

6.21"

October

7.06"

November

1.96"

(Eagle Knob Snowfall: 0.5")

Autumn 2020

(1 Sep-31 Oct)

15.23"

December

6.22"

(Eagle Knob Snowfall: 34.0")

2020 Total: 96.80" (M)

(January 1 to December 31 Period)

2021

January

6.35"

***(Eagle Knob Snowfall: 34.0")

February

7.42"

(Eagle Knob Snowfall: 19.5")

Winter 2020-21

(1 Dec to 28 Feb)

19.99"

(21.70" on Eagle Knob)

March

10.82"

(11.14" to Midnight 31st)

April

2.53"

(Eagle Knob Snowfall: 2.5")

May

4.54"

(Eagle Knob Snowfall: Trace)

Spring 2021

(1 Mar-31 May)

17.89"

June

4.79"

July

5.55"

August

10.39"

Summer 2021

(1 June-31 August)

20.73"

September

5.82"

October

3.80"

November

2.23"

(Eagle Knob Snowfall: 1.5")

3 days with 1" or more depth

Autumn 2021

(1 Sep-30 Nov)

11.85"

December

4.63"

(Eagle Knob Snowfall: 1.0")

Several days with Trace depths

2021 Total: 68.87"

(January 1 to December 31 Period)

2022

January

8.74"

(Eagle Knob Snowfall: 40.0")

29 days with 1" or more depth

February

10.32"

(Eagle Knob Snowfall: 3.5")

14 days with 1" or more depth

November 2019-October 2020: 102.34"

Autumn 2018 to Summer 2019: 91.21"

Autumn 2019 to Summer 2020: 94.44"

Autumn 2020 to Summer 2021: 73.84"

(M): Some missing moisture in undercatch and frozen precipitation, with partial corrections applied for the 24.4 meter (80 feet) tall dam structure where rain gauges are located. Corrections are based upon 86-months of direct comparisons between NWS and IFLOWS at Big Cherry Dam (including occasional snow core-water content data).

26 February 2022 at 2:18 PM

High Country of High Knob Massif

Looking Into Big Cherry Lake Basin

Cody Blankenbecler Image © All Rights Reserved

This recent pattern has increased already huge precipitation differences across Virginia between the High Knob Massif and the New River and Shenandoah River valleys.

(28 February 2022)

Big Cherry Dam

Today: 0.00

Month To Date: 10.32

Since DEC 1: 23.69

Since JAN 1: 19.06

For comparison:

Blacksburg, Virginia

While southwestern Virginia has received a general 2-5 times the average precipitation during the past 7-days, portions of central and eastern Virginia had only a quarter to one-half as much as their average for this time of year.

19-26 February 2022

Percent of Normal During Past 7-Days

26 February 2022 at 2:08 PM

High Country of High Knob Massif

Looking Across High Knob Lake Basin

Cody Blankenbecler Image © All Rights Reserved

Hydrology of February 2022

February 2022

Big Stony Creek of High Knob Massif

Whitewater creeks draining the High Knob high country dissipate a tremendous amount of energy as water levels rise above 3 to 4 vertical feet on the Big Stony Creek gage, with direct correlations to the South Fork of Powell River, Clear Creek, Little Stony Creek, Cove Creek, Stock Creek, Burns Creek and many others when precipitation and/or snowpack melt is widespread.

Abundant run-off dominated the month, with

two major periods at the beginning and end that generated prolonged ROARing water levels.

28 January-28 February 2022

Clinch River at Speers Ferry

While the highest peak occurred on headwater steep creeks during 4 February, with a combination of rain and snowpack melt, highest levels on main-stem rivers were observed on 25 February.

Whitewater Draining High Knob Massif

Wayne Browning Photograph © All Rights Reserved

Evolution of hydrological networks within the

High Knob Massif are a product of interrelated systems that undergo self-organization across space and time.

The sound of ROARing water and perceptible vibration of the ground when near these steep creeks is part of this self-organizing system.

Energy = Power X Time ==> Power = Energy / Time

The above further implies that Power = Work done per unit Time given that Energy = Work, where the rate of using energy is equal to the rate of doing work.

Since the discovery of deterministic chaos by Edward Lorenz in 1963, an increasing focus on the nonlinear nature of geomorphic systems has led to the recognition that system outputs (responses to inputs) are often not proportional to system forcings (inputs). This is a

classic characteristic of complex systems.

Theoretically, this wettest terrain in Virginia should accomplish the greatest amount of work as the largest energy input in the state is dissipated per unit area across space and time.

Observed Climatology

of February Wetness

2018-2019-2020

500 MB Height Anomaly Pattern

Heavy to excessive February precipitation has

high correlation to a ridge-trough-ridge pattern that develops across North Ameria and the Northern Hemisphere.

February 2022

500 MB Height Anomaly Pattern

The main difference between the February 2022 pattern (above) and that during the previous three wettest February's of recent years is that the ridge-trough-ridge pattern was a little farther east.

2018-2019-2020

500 MB Height Anomaly Pattern

A composite mean of the four wettest February's of recent years, that generated an average of 12.55" at Big Cherry Dam (2018-2019-2020-2022), continues to produce a strong climatological signal (below).

2018-2019-2020-2022

500 MB Height Anomaly Pattern

Interestingly, the observed increase in total February precipitation during 2018, 2019, 2020, 2022 was 166% at Big Cherry Lake Dam and

164% at Blacksburg in the New River Valley.

2018, 2019, 2020, 2022

Four Year February Mean

Blacksburg NWSO: 4.64"

Big Cherry Dam: 12.55"

Actual means, however, were radically different

(as previously highlighted) between these two sites.

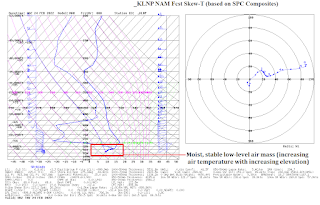

925 MB Vector Wind

Compsite Mean February 2022

Clearly, there is much more than just the upper air pattern working to cause such huge precipitation differences. To better understand this a look at

the orographics are in order.

A 925 MB flow trajectory was chosen given it is in between the surface and 850 MB, near the middle of mean surface-850 layer air flow across the terrain.

925 MB Vector Wind

Composite Mean 2018, 2019, 2020, 2022

Mean air flow trajectories streaming into the

High Knob Massif do not encounter any higher mountains upstream, prior to reaching the lofty basin of Big Cherry Lake, as they flow through

the Great Valley of eastern Tennessee.

2018, 2019, 2020, 2022

Approximate 925 MB Composite Mean

February Trajectory Into High Knob Massif

Base Map Courtesy of Macrostrat

This setting is radically different from air flowing into the New River Valley on this type of mean SSW-SW trajectory.

2018, 2019, 2020, 2022

Approximate 925 MB Composite Mean

February Trajectory Into New River Valley

Base Map Courtesy of Macrostrat

Moisture extraction downstream of mountains along the Tennessee-North Carolina border, and northern Georgia, reduces moisture available for lifting and precipitation even at higher elevations surrounding the New River Valley on this type of air flow trajectory.

An Orographic Forcing Perspective

Climatology of the Southern Appalachians

I highlighted this aspect in a graduate school video, along with other factors that collectively have large influences on Virginia climatology (and therefore, interconnected geomorphology and biodiversity).

Meteorological Winter 2021-22

Orographic Precipitation Differences

925 MB Vector Wind

Compsite Mean Dec-Feb 2021-22

Nearly the same type of mean low-level flow in

the Meteorological Winter period of December-February was impacted by the same type of orographics, with large differences observed

from west to east across southwest Virginia.

December-February Period

Superimposed upon regional orographics are

local impacts that generate large gradients, as exemplified by precipitation differences between the High Knob high country and lower-middle elevations across Dickenson-Wise-Buchanan counties downstream of the massif.

Base Map Courtesy of Macrostrat

During the December 2021 to February 2022 period of Meteorological Winter, the Levisa Fork Valley in Grundy received only around half as much precipitation as Big Cherry Dam along

a mean airflow trajectory that approximately followed this terrain cross-section (above).

Taking flow trajectories observed during every day from

1 December to 28 February, adding them up and deriving

a composite mean for the entire 3-month period.

Recent Example

High Knob Massif

Orographic Capping Pilatus Cloud Deck

It must again be stressed that much more than just vertical elevation is at work, with extensive capping pilatus (orographic feeder) clouds vital to enhanced precipitation reaching the surface across the

High Knob Massif.